Recently, the players of “Twitch Plays Pokémon”

beat the game. As fellow classmate, Greg Palermo stated, “The premise is that a bunch of people (reportedly as many as 50,000) control the character 24-7 through a text feed–in other words, by typing “Up,” “Down,” “Left,” “Right,” “A,” “B,” etc.–and try to see if they can actually get anything done.”

It is reported that it took the thousands of players a total of 390 hours to complete the game.

This “social experiment” has led me to look upon past gaming systems their evolution.

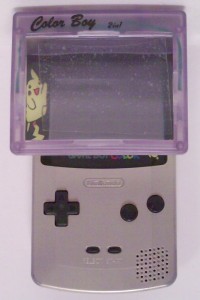

My first interaction with video games was over a decade ago (wow I feel old!). The Gameboy Color let children escape into many different worlds such as Super Mario Bros., Donkey Kong, and the notorious Pokémon. There were many accessories for the Gameboy Colors, such as the

nifty light that helped when playing under the covers past your bedtime. In addition, there was the magnifier. I remember

nifty light that helped when playing under the covers past your bedtime. In addition, there was the magnifier. I remember

thinking how amazing this gaming system was with its accessories. I loved the fact that in an instant I could be riding around on Yoshi or avoiding barrels in Donkey Kong while trying to save the Princess. Playing on my Gameboy Color was the time for my own personal entertainment, in solitary.

Children began individually playing with their Gameboy Color in groups during recess or play

dates. It was inevitable that the creators of Gameboy created a way for users to change the gaming experience and play together. The Gameboy Link Cable made it possible for individual users to interact with each other within the same game. This was brand new and amazed many. The old solitary style of playing video games was slowly becoming extinct.

Years later, Xbox 360 was one gaming platform that came out with the brand new feature of users talking to each other from anywhere in the country via headset. This allowed players to interact more than ever before and paved the way for more mass gaming experiences.

“Twitch Plays Pokémon” seems incredible to our generation now because of its premise of linked mass contributions with one goal. Years ago, while I was under the covers with my “worm light” attachment, I would have never guessed that Pokémon would be on the computer, let alone be played by thousands of nerds all over the world.

This achievement and disbelief reminds me of Henry David Thoreau’s statement from “Walden:” “Old deeds for old people and new deeds for new.”

I remember my parents being amazed by all my video games, from the Gameboy Color to the Wii; I guess I’ll have to wait and see what my child will surprise me with!