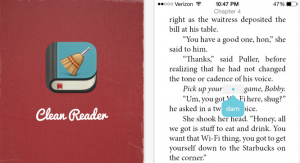

More and more information and literature is available to us through only few clicks or swipes thanks to resources such as the Digital Public Library of America and Project Gutenberg, but today’s ever-evolving technology can also allow for censorship of these materials. Clean Reader is a fairly new e-reader app that allows readers to censor swearwords and other offensive phrases from books purchased through the app’s online bookstore. A recent article from the Guardian goes into further depth about the app, created by the mother and father of a young student in Idaho.

While the app received positive feedback initially, as indicated in the initial article, the tide soon turned as authors began to notice that their work was being censored. Less than two weeks after the publication of this article, another was posted about the outcry from the censored authors. Fittingly, most of the protests came from Twitter and blogs, as has become the norm in today’s digital world.

Hate the book. Ignore the book. Burn the book. Tear up the book. Just don’t try to rewrite the book. #CleanReader

— Joanne Harris (@Joannechocolat) March 25, 2015

My $.02 on #CleanReader… . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Oh, you couldn’t read my opinion, my words? Blame #CleanReader!

— Debra Kayn (@DebraKayn) March 25, 2015

#CleanReader would turn the act of “breastfeeding” into the far creepier-sounding “chestfeeding.” “FEED FROM MY CHEST, PROGENY.”

— Chuck Wendig (@ChuckWendig) March 26, 2015

These very public objections have led the founders of Clean Reader to remove the books that belong to the Inktera and Smashwords bookselling systems, as well as those of several other authors, from their bookstore. The removal of these books has been seemingly swift and fairly painless. Author Joanne Harris, one of the app’s biggest opponents, considered this a win, telling the Guardian, ” It is a small victory for the world of dirt. And a wise move on their behalf. I think somebody would have proved how fundamentally illegal it is, and would have taken them to court … it’s interesting to see how pressure from the internet has done it, and how widespread support is for the integrity of books. A lot of people don’t want to see books tampered with.”

Authorial intention seems to be an underlying issue of the controversial Clean Reader app. Many of the supporters of the app don’t believe the author’s intentions are significant in reading a book, and feel that once a book is published, readers can do with it what they please, and this apparently includes changing words in the text. Most of the authors seem to align with Harris, whose opinion is clearly the opposite. Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and other forms of social media have made knowing an author’s intentions much easier than in the past. While we rely on Thoreau’s journals, correspondence, and revisions to attempt to understand his intent in writing Walden, many authors today will directly answer questions from their readers through various social media platforms. Whether or not this is a good thing is debatable, but in the case of Clean Reader, I feel it is a positive.