19th century American women writers received plenty of disapproval and even derision for their work during their lifetimes, and their texts were often placed into boxes – domesticity, sentimentality – that may not be fair representations of what they were really interested in writing about. Take Nathaniel Hawthorne’s biting remark about his female contemporaries as an encapsulation of this attitude:

“America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash-and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed.”

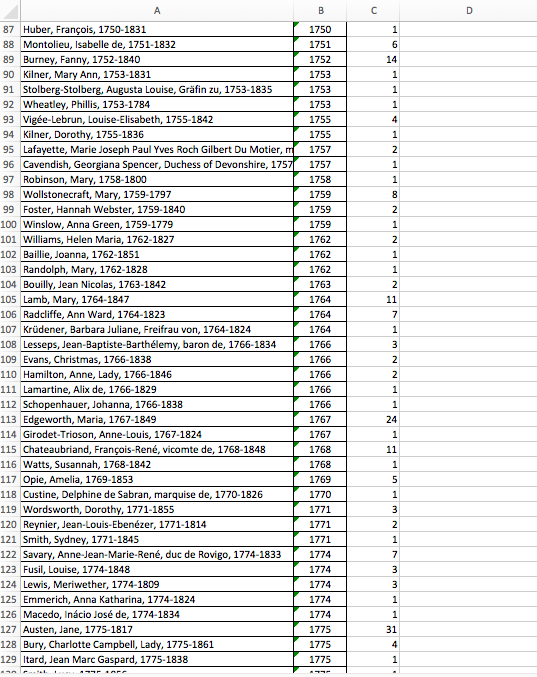

With this in mind, I aimed to perform a textual analysis in two parts: on an individual author basis, with five selected writers I have studied in the past year, and on a macro level, with a larger sample of women’s writing from this period being gathered together for a much more distant read. My intention was to identify patterns throughout these texts that, for the individual authors, indicate the weighty social issues being address (slavery, education, law, and economic empowerment are big ones), and for the macro-level analysis, show us how sentimental their writing may be.

Analyzing the language of texts is a very traditional humanities aim; essentially, I’m performing the age-old task of drawing connections between a piece of literature and its historical and social contexts, as well as challenging preconceptions about who we read and why. Where this project really differs from traditional scholarly efforts to read and understand texts is in the way it analyzes literature. Instead of performing a close reading, I’m using digital tools to “distantly” read literature – pulling out patterns and data that may suggest what writers are focused on without necessarily having a strong, intimate understanding of the individual text. This reading also allows humanists to evaluate an entire subset of writing – the nineteenth century, women, etc. – and find intriguing results to further evaluate, rather than build an understanding from the ground up by developing an expertise in specific works of literature.

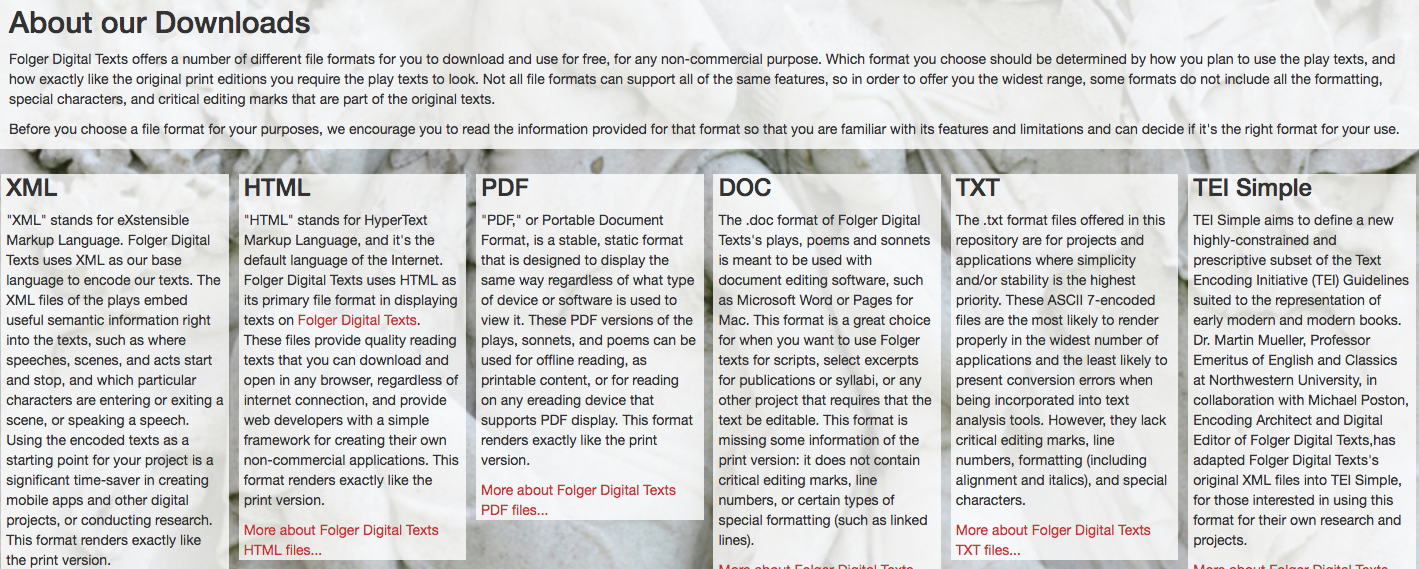

This work was all compiled on a WordPress site, which went through a few different themes before I settled on one that would provide the easiest navigation for visitors – a side menu bar with the various options listed in full as readers are scrolling down each page, paired with a top menu that also shows where these pages can be found at a glimpse. I was also aware that I didn’t have too many eye-grabbing images to include, so I needed a more text-centric theme that was still appealing to visitors.

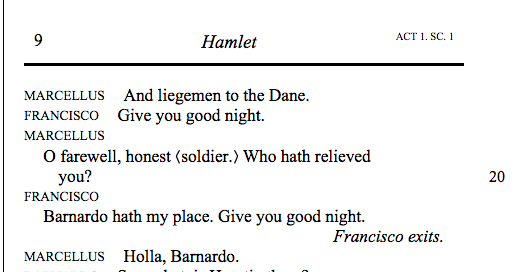

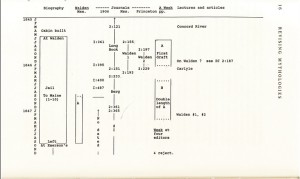

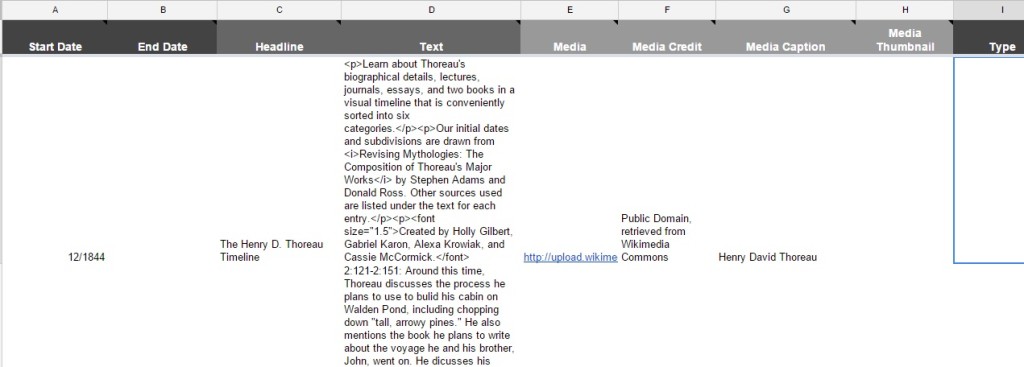

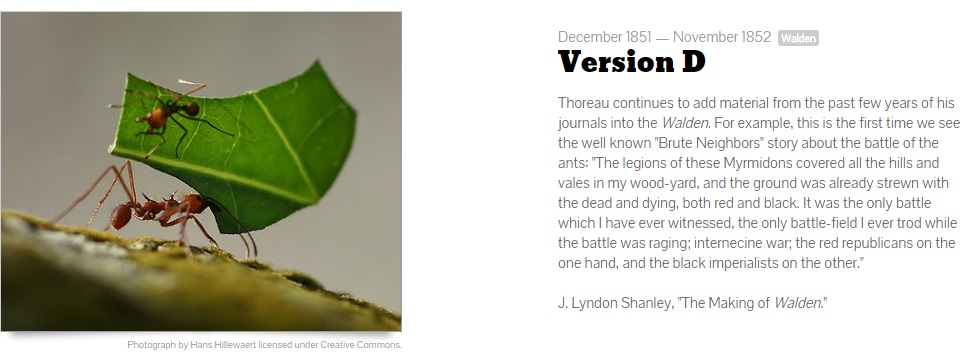

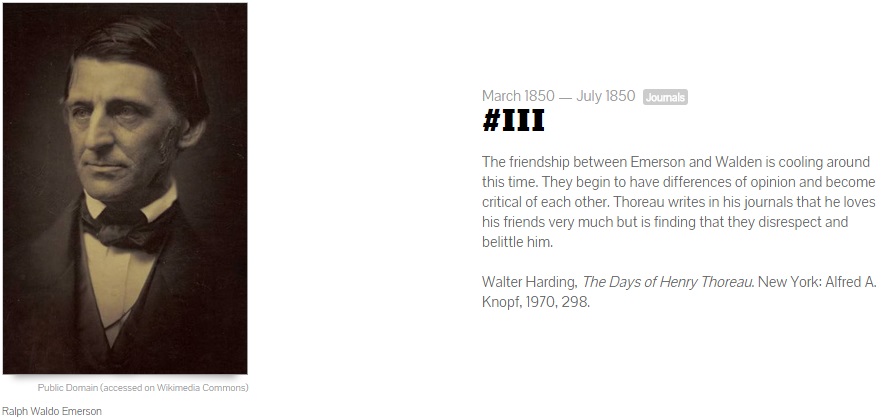

The first page users will come across is the welcome page, which introduces the project, addresses its impact, and briefly points to some of the conclusions that can be found in the analysis pages of the site. I’ve also incorporated an overview of the texts being individually analyzed in a Timeline JS timeline, which can be seen below:

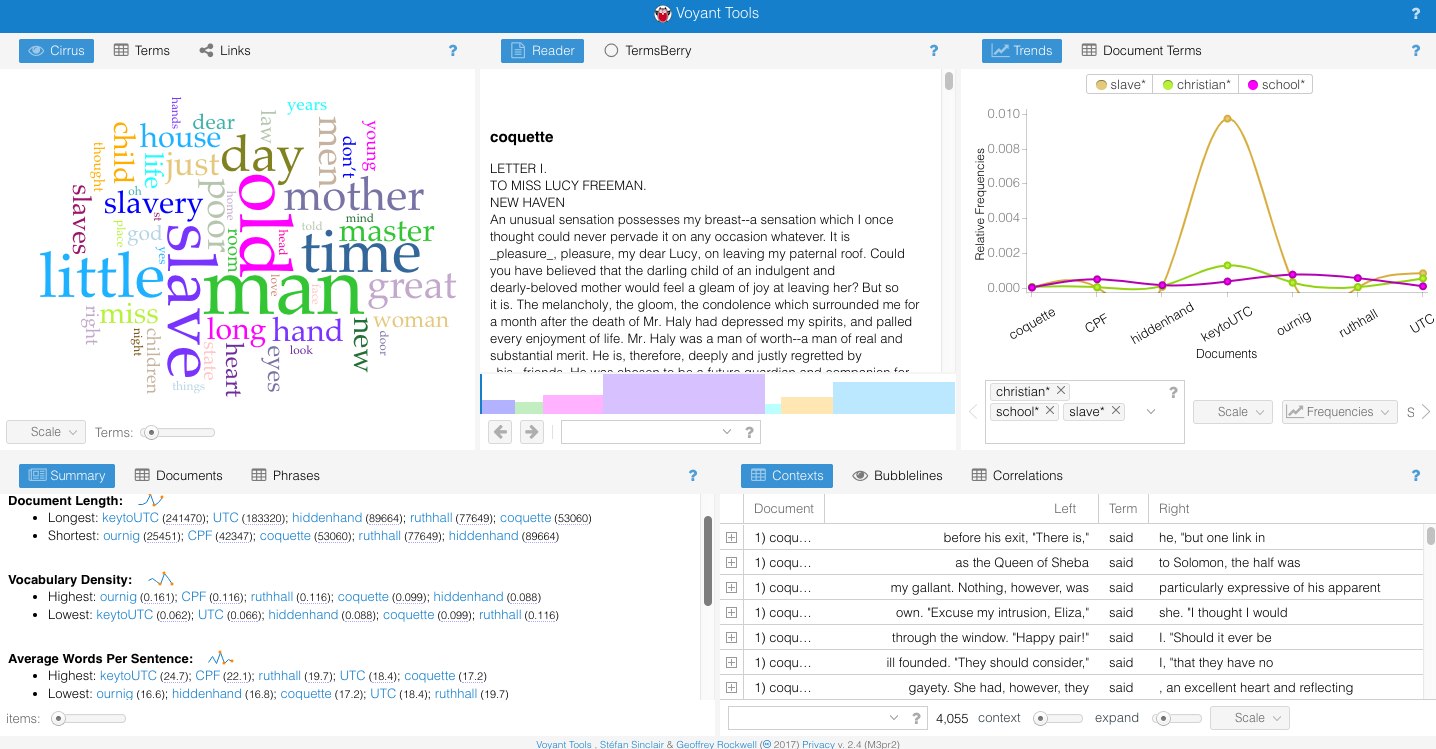

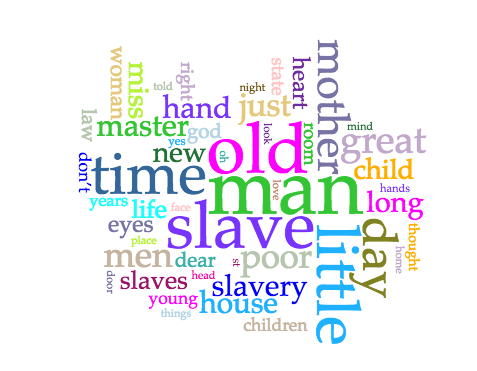

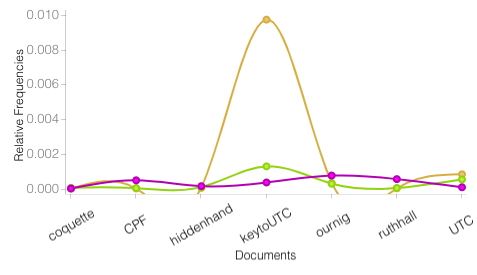

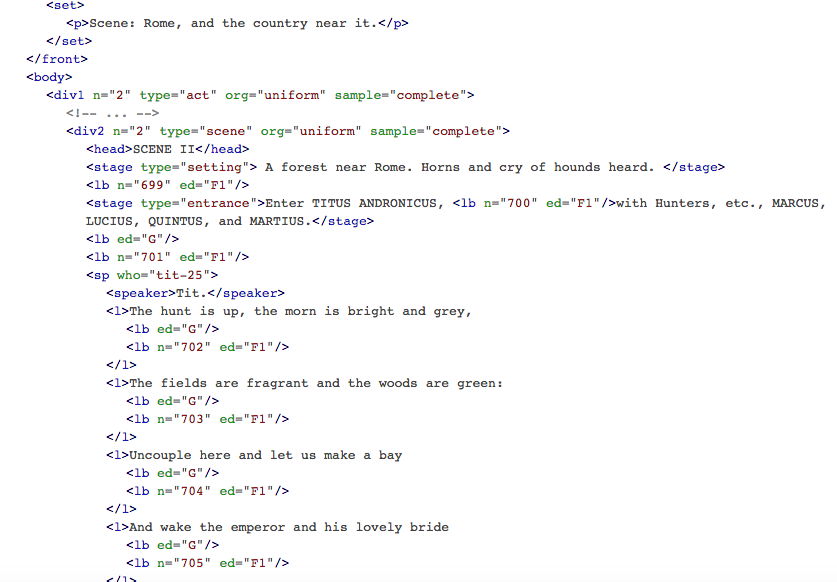

My intention is that users will first, if interested, look through the author analysis pages in order to learn more about each of the women’s writings I selected. On each page, I include a brief introduction of the writer, and then the text analysis put in context with my own close reading of the novels or other pieces being examined. For the analysis, I used Voyant Tools, a free online resource that allows users to upload text files and analyze them in a variety of ways – for my purposes, I mainly used Word Cloud, which is a visual representation of word frequencies, and Trends, which creates a graph tracking the relative frequency of specified words across one or multiple texts.

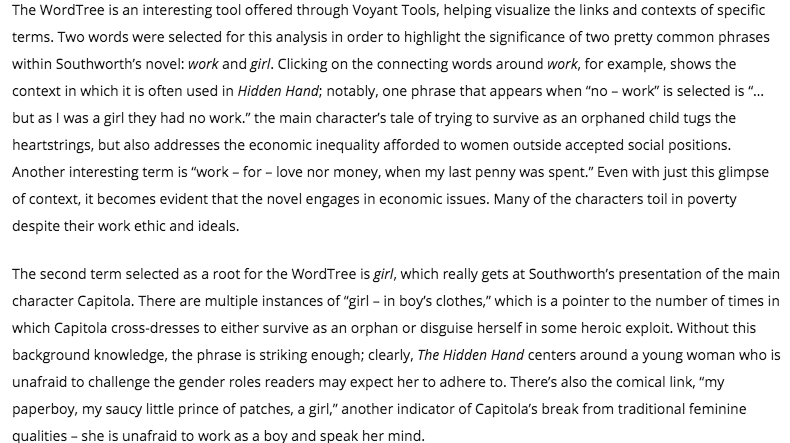

The best way I found to represent these results was to embed them directly from Voyant Tools, which allows users to interact with the graphs rather than just view them as an image. This has the potential to create issues with my project – it’s unclear how permanent these embeds are, since they’re hosted by Voyant Tools itself. So far, it’s been a couple of months and there have been no complications from this, but I did save the graphs as PNG images just in case I need to insert those instead. The benefits of the embedding can best be seen in the Word Tree chart I used for E.D.E.N. Southworth’s The Hidden Hand – with this tool, users can click on selected words to see their linkages and contexts. Try it for yourself below, and explore Southworth’s usages of the terms girl and work.

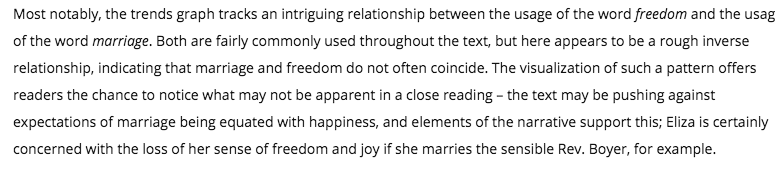

As a whole, I found some really interesting patterns using Voyant Tools on the smaller-scale level. Although I cannot include all the author analysis pages on this post, Hannah Webster Foster’s Trends chart is another example of the conclusions that may be drawn using digital tools.

Here, I’ve embedded the Trends chart from this page. Although readers can see what they find on their own by clicking through it, I’ve also included my own analysis:

The visualization of the pattern discussed above offers readers the chance to notice what may not be apparent in a close reading, or understand how Foster might be pushing against social norms even if they haven’t had the opportunity to read her novel The Coquette for themselves.

The visualization of the pattern discussed above offers readers the chance to notice what may not be apparent in a close reading, or understand how Foster might be pushing against social norms even if they haven’t had the opportunity to read her novel The Coquette for themselves.

The second part of my project is the macro analysis, and the best description of how this was developed can be found right in its page on the WordPress site:

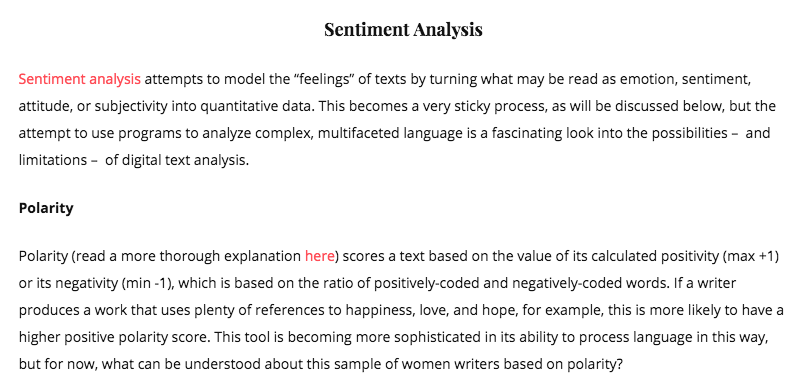

Sentiment analysis became a major focus for this part of the project – using digital tools to evaluate the emotions, positivity, subjectivity, and other non-quantitative aspects of a piece of writing. Polarity is one of the key aspects of sentiment analysis, and what I’ll be using here to demonstrate some of the difficulty I’ve had in drawing conclusions from such a tricky tool. For a description of sentiment analysis and some of its issues, read another excerpt from the project:

Here, I’ve embedded the line chart that has been produced from Kirk’s data on the polarity of these nineteenth-century American women writers, and also shared my interpretation of it below. As noted, a higher positive value indicates a more positive use of language (closer to +!), while -1 represents max negativity.

Here, I’ve embedded the line chart that has been produced from Kirk’s data on the polarity of these nineteenth-century American women writers, and also shared my interpretation of it below. As noted, a higher positive value indicates a more positive use of language (closer to +!), while -1 represents max negativity.

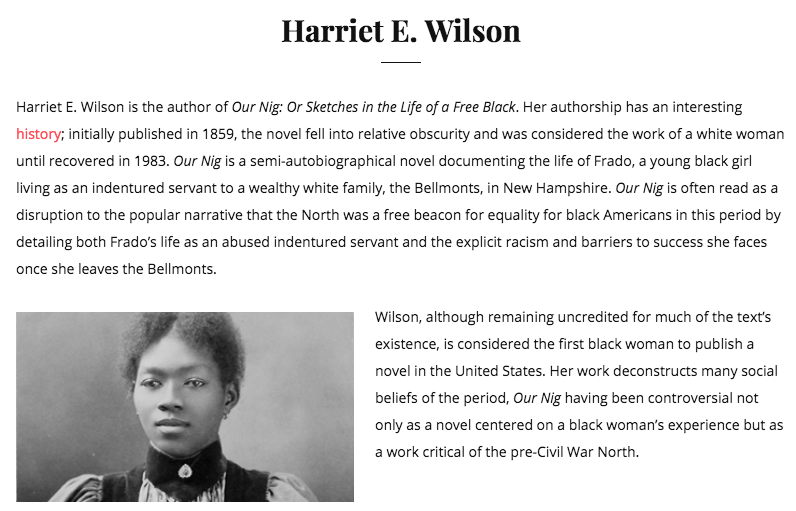

Text analysis was a much more conceptually simple tool when I was using it to evaluate individual texts that I was already quite familiar with, and I think the context I lend the graphs in my individual author pages help readers draw significant conclusions – yes, women writers in this time were interested in some pretty major and controversial national debates. Harriet Beecher Stowe, for example, wrote one of the most influential abolitionist works in our nation’s history, but my site also lets these results be read alongside the less well-known Harriet E. Wilson’s examination of the same issue in a much different context:

The macro analysis is inherently more problematic, but I end my project with the conclusion that sentiment analysis can offer humanists potential directions to take future work. I can’t make decisive conclusions just from the polarity and subjectivity results in the scope of my project, but they would have much more meaning if compared with the same values from a sample of men’s writing, or even from a sample of twentieth-century women writers. There are so many directions to take this kind of work, and I think my project succeeds in at least addressing this possibility. This has been a conceptually challenging undertaking, but over the course of the semester, I’ve been able to not only increase my technical skills (building a WordPress, performing some basic text analysis, doing plenty of embedding) but also my theoretical understanding of how humanists can use digital tools and technical, quantitative analysis to draw conclusions about literature.