It’s 2015 and I’m a college student. Naturally, the first place I go with any question on the signatories of the Treaty of Westphalia, a quick biography of Robert De Niro or a quick history of Tesla Motors is Wikipedia.

Indeed, in writing this post, the first place I went to for information on Wikipedia was Wikipedia itself. The second place? Google, of course.

Given the dominating presence of wikipedia in my own life, epistemological questions about who writes, or perhaps who edits, are of significant concern.

Wikipedia is huge. in 2014, The New York Times reported that “With 18 billion page views and nearly 500 million unique visitors a month, according to the ratings firm comScore, Wikipedia trails just Yahoo, Facebook, Microsoft and Google, the largest with 1.2 billion unique visitors.” Wikipedia then, has become a central source of information for huge numbers of people worldwide. Google’s statistics indicate 1.2 billion unique visitors searching for anything; Wikipedia has nearly half as many unique visitors a month searching specifically the encyclopedia-esque content available on the site.

What’s more, Wikipedia has significant repeat visitors. Wikipedia’s own metadata from 2011 indicates that nearly half of those 500 million unique monthly visitors revisit at least 5 more times that month. So for 250 million people a month, Wikipedia is a primary source of information, which they visit at roughly half the rate they Google search. For anything.

All of this means that Wikipedia’s impact on knowledge, who has access to that knowledge, and especially the quality of that knowledge is massive.

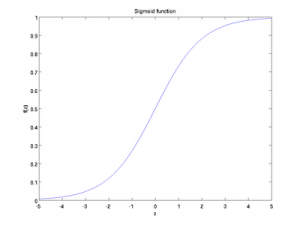

A bit of background on the way encyclopedias function: In their early stages, and this is especially true of an online crowdsourced encyclopedia that started from nothing, the growth is similar to a sigmoid function. When the site starts, edits happen slowly at first, then rapidly as the pages are added to create a corpus of information until a climax point is reached, at which point essentially everything worth creating has been created, aside for new pages whose necessity emerges over time.

This understanding was confirmed by Wikipedia’s most prolific editor, Justin Knapp: “The number of editors as such is not necessarily a problem — eventually, the content of the encyclopedia will become more-or-less complete and what’s required is curation and maintenance. By the time you get to 4 million articles in one language, it’s close to done in terms of adding new articles.”

Still, this only answers questions about the statistical patterns in editorship. What of the people who are doing the editing?

In the last two years, there have been three episodes in particular that have called into question the biases of Wikipedia.

The first, an op-ed posted by New York Times writer Amanda Filipacchi entitled “Wikipedia’s Sexism Towards Female Novelists,” pointed out the flaws in Wikipedia’s list-based organizational system. The second big issue was the “Gamergate” controversy, centered around sexism and “gamer” identity in the video game community. Finally, the NYPD’s edits of Eric Garner’s page was met with some serious criticism.

In the first two instances, Wikipedia’s gender bias is of primary concern. Wikipedia itself has admitted to being composed of anywhere from 87-90% male editors, which have led to claims of systemic male bias on the site. Wikipedia has identified the issue, and notes it on its own “Criticism of Wikipedia” page.

Two major publications have taken on the issue of gender bias on Wikipedia, and what the Wikimedia Foundation and the Arbitration Committee, as well as outside groups, have done to try to remedy the issue. I could summarize the process, but instead I recommend checking out these two excellent pieces: The Atlantic on the issue. MIT Technology Review on the issue.

The MIT Technology Review, in particular, points out the problems with the democratic ideals that spurred Wikipedia’s creation. Unfortunately, Simonite claims, closing the gender gap has been complicated by “The loose collective running the site today, estimated to be 90 percent male, [which] operates a crushing bureaucracy with an often abrasive atmosphere that deters newcomers who might increase participation in Wikipedia and broaden its coverage.”

Throughout my academic life, when teachers and professors advised me against using Wikipedia as a source, these issues of systemic bias and the complications they have to the question of “Who Speaks?” never crossed my mind. Instead, I was instilled with a hesitation to take Wikipedia as fact. Ultimately, I have found, the issues with editorship on Wikipedia are not of accuracy, but of equality and government intervention.