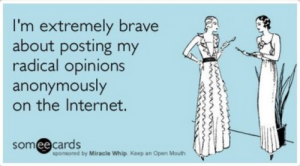

In part because I’m still thinking about Katie Bockino’s The Creepy Side of Technology?, and in part because I recently changed all my passwords (thanks a lot, Heartbleed) and downloaded a new app to store them in, I’ve been reflecting on some of the apps available and wondering about their place in our lives. “Tool time” is one of my favorite Digital Humanities activities, so rather than sharing actually useful apps for fear of stealing someone’s thunder, I’m only going to share apps I’ve found that fall under one of the following categories: funny, creepy, scary but possibly helpful, genius, and but… why? In a way, I think analyzing the logic behind some of these and wondering what this says about our culture might be even more telling (and fun) than looking at the productive tools which now exist.

Funny

For the arrogant, self-righteous teens in our lives, the Annoy-A-Teen app allows an adult user to inconspicuously broadcast high-pitched sounds that can only be heard by younger ears. It just annoys those who can hear the frequencies, and they likely won’t be able to tell where the noise is coming from.

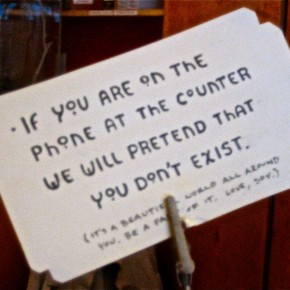

For those who can’t control themselves (while drinking or otherwise), there’s Bad Decision Blocker, which allows a user to predetermine at the beginning of the night which contacts should be blocked and for what amount of time. No more regrettable booty calls, butt dials to one’s boss at 2 AM, or temptation to call up one’s ex. I even remember reading somewhere that breathalyzer apps either are or will be available, checking the blood alcohol content of a user before they get behind the wheel.

My analysis: The Annoy-A-Teen app is obviously meant to be light-hearted and tells us nothing new about teen/adult relationships; teens have always been right, and adults have always been idiots with the job of making teens’ lives more difficult or embarrassing. Duh. But the Bad Decision Blocker interests me because like many current apps, it aids with the self-control of adults. This is not to say adults have never struggled with self-control before now, but I think this is becoming more of a public rather than a private issue. In other times, having little self-control was seen as a weakness or as immaturity, but now I think our society regards it as part of being “human” and has ways of assisting those of us who need a little help, particularly when under the influence.

Creepy

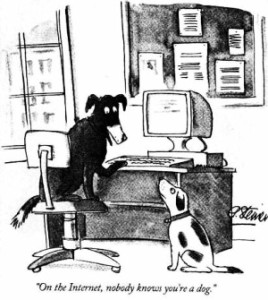

SpCam is an app that allows users to track any motion or sound that happens in a room, and is meant for when users are away from their device. Though I suppose it could work on a phone, it was meant for computers, and aids a user in discovering who was near (or even on) their computer while they were away, and what this person was doing.

For the Creepy McCreepsters who are “in the mood for love” or “just after a one-night stand” (can’t even make this stuff up, it’s on the site) Girls Around Me is an app that allows users to see pictures, get information about, and even make unsolicited contact with females who have used apps like Foursquare to check in at nearby locations. It also has a function to see the current male-to-female ratio of a spot, giving users better chances of achieving their goals.

The Recognizr app takes stalking to a whole new level! The app employs face recognition technology to identify strangers with the camera function on a user’s phone: “Face recognition software creates a 3-D model of the person’s mug and sends it across a server where it’s matched with an identity in the database. A cloud server conducts the facial recognition… and sends back the subject’s name as well as links to any social networking sites the person has provided access to” (Huffington Post).

My analysis: Well, we can’t say we didn’t see these things coming. As we all learned from Spiderman, with great power comes great responsibility. Even well-intentioned technology like the cameras in our phones or computers can be used maliciously when the right app is installed. Do apps like these warrant all of us to become paranoid about our safety and privacy? Maybe. But hopefully with some common sense, intuition, and dependable girlfriends, a woman in a bar will be leery of the man who seems to know a little more about her than he should.

Scary but Possibly Helpful

Two mind-altering apps available today are Brainwaves and Hypnosis. Brainwaves is made by the folks at the trustworthy “Unexplainable Store” and is said to aid users in “Spiritual, Meditation, Sleep, Relaxation, Positive Life, [and] Brain Training.” The Hypnosis app promotes an easy method of losing weight.

Type n Walk is “the smarter, safer way” to text while a user walks. It works by making a user’s screen appear as a dim version of exactly what is in front of them, and the text appears in front of that translucent rendering.

For the parents who just don’t want to spend time getting to know their baby, or are otherwise concerned that picking the baby up might not be one in-the-meantime solution, there’s Cry Translator. Simply click on the app, wait for it to load, hit the listen button (it’s like Shazam for crying babies!), let Cry Translator listen to your baby crying for at least 10 seconds, and wait for the app to tell you what – in its expert opinion and with all its knowledge of your particular baby – needs. Then the user responds appropriately.

My analysis: Frankly, Brainwaves and Hypnosis kind of freak me out. There is so much unconscious stuff happening in my brain already, the last thing I want to do is allow more out-of-my-control processes to happen. No way, Jose. Type n Walk: Or, you know, someone could glance up every few seconds or maybe even pay attention to where they’re going. What’s next, Type n Sports? Type n Drive? Type n Surgery? Cry Translator makes ME want to cry, I mean really, babies are rarely upset for a reason that is so unexplainable, we need to call in expert technology for backup. Maybe try picking them up first. Then go through the usual checklist: diaper, hungry, tired, bored, teething, sick, got scared by a loud noise, etc. It’s not that hard, people.

Genius

Fake-an-Excuse: Hang up Now! features a variety of lifelike excuses a user might need to get off the phone with someone. Annoying mother-in-law? Try the “call waiting beep!” Hot mess friend after a break up? Try the “I hit a mailbox with my car” sound. Others include “Someone’s Here (knocking or door bell sounds),” “I’m Being Pulled Over (siren),” and “Bees! They are Everywhere, (buzzing).”

Another genius app based on sound effects is iNap@Work, particularly useful for the employee stationed near his boss’ office. This app allows users to choose from work noises like a mouse clicking, a keyboard typing, papers crumpling, other office sounds (stapler, pencil sharpener), blowing one’s nose, clearing one’s throat, etc.

My analysis: Are these apps kind of sketchy and devious? Absolutely. But sometimes, they are necessary evils for a user to maintain her sanity and/or get in a few minutes of needed rest. What do they say about our society? Sometimes we are unable to be honest with people and wish to spare their feelings (or retribution), so we protect ourselves with these apps made by really smart people who understand our dilemmas.

But… Why?

In my quest for interesting apps, I found WAY more – and I mean a stupid amount – of apps having to do with bowel movements. Places I’ve Pooped and Bowel Mover Pro are among them.

EMF Meter is the perfect app for when you’re, you know, looking for ghosts and other paranormal stuff.

Lastly, where was the Great Pumpkin Weight Estimator app when I needed it? I can’t tell you how often I would have used this if I had known about it sooner.

My analysis: I’ve got nothing.

Well, it’s inevitable that along with all of the great apps out there that help us stay organized and productive, help us do everyday things more easily, and help keep us happy and entertained, there are bound to be those that make us scratch our heads in wonder. I don’t think any of the apps I’ve mentioned have anything profound to say about our society, except to maybe highlight different idiosyncrasies that have always existed among us in more publicly scrutinizing ways.