This past summer I spent a bit of time volunteering for an organization called Literacy Volunteers of Greater Syracuse. When I came in the office for an interview, the woman running the program was ecstatic that she had an inexperienced, untrained 20-year-old come in to help teach illiterate adults who need to learn to read to find a job. Why?

Because I’m young and, therefore, “naturally understand the internet.”

Being a member of this generation put me in a position of privilege I didn’t know I had and had never really appreciated before. I was placed in a program geared toward digital literacy that works one-on-one with clients in a computer lab. The program is very much tailored to the client’s needs, ability, and interest. What I mean here is that it can range from setting up a facebook account to write to their grandchildren to how to move a mouse and turn a computer on and off.

The client I worked the most with was a 60-year-old man from the city of Syracuse. He told me that he never did well in school (from my short time with him I’d guess he had dyslexia or another type of mild learning disability) and had to drop out after 3rd grade. It wasn’t a problem ~50 years ago though, and he had an easy time finding a job working in an airplane part factory. He said that he never had any incentive to learn how to read, because he knew how to do his job well, and could learn by watching other people. Then, this year, when he was only a few years about from retirement, his company shut down and he was left without a job in a market that was vastly different from the one he knew.

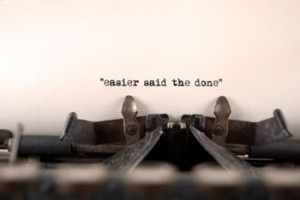

My client vowed he would take 2 years off to learn how to read and get his GED so he could find something else to do for the last few years before retirement. However, he quickly realized that wasn’t going to be enough. Most job applications are online now, and employers want to communicate via email. What’s the point of learning how to read/write in this day and age if you can’t Google search or type? A lot of resources LVGS uses to help people are websites such as USA Learns, which use games, quizzes, videos, etc to supplement their tutoring, and make it more interesting. None of this is accessible to someone who has low literacy AND low digital literacy, and what I found is these often go hand-in-hand. And this just reinforces the idea for me that nowadays reading/writing are inextricably linked to our screens and keyboards.

I guess technology and literacy have always been intertwined. How much good would it have done you 20 years ago to know your numbers if you couldn’t dial a telephone? But in this particular moment it seems especially crucial to be literate not just in a “knowing how to read” sense, but in a “knowing how to read in different contexts” sense. I’ve been thinking this in class as we wade through learning about XML, blogging, online texts, etc. I mean, why isn’t that sort of knowledge part of a well-rounded education, whether at the primary or secondary level? As important as it was for my client to learn how to email hand in hand with learning how to write, it seems important for English majors to learn how to access digital texts while learning how to read critically.

So, my time tutoring was very eye-opening as to the idea of the internet/digital world as a collaborative space. This space is becoming as important to access as a pencil and paper were in the past, for many reasons. I see this future of English classes as emphasizing what is done online, and becoming intertwined with what my high school called “computer class,” because really, what can one be without the other?

Does anyone have any thoughts? 🙂