The Beginning of the End of Online Commenting?

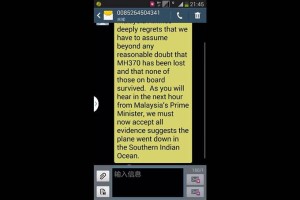

In a recent class discussion, we touched on the topics of censorship, relevancy, equality, and anonymity when thinking about who should have a voice in certain online situations and what they should be allowed to share. USA Today published an article earlier this week called “Online commenting: A right to remain anonymous?“, which addresses some of these issues. The piece talks about how Internet culture has been forced to change in light of the way users are behaving; in the second half of 2013, The Huffington Post opted to ban anonymous comments from its site, and Popular Science surprisingly stopped allowing any form of commenting whatsoever. According to the USA Today article, this shift was in an attempt to “breathe civility back into what many see as the Wild West of the Web.”

But Does Banning or Censoring Comments Solve the Problem?

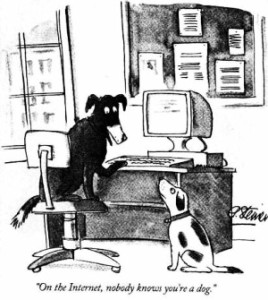

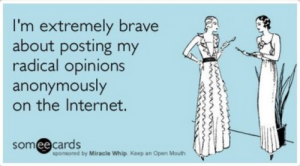

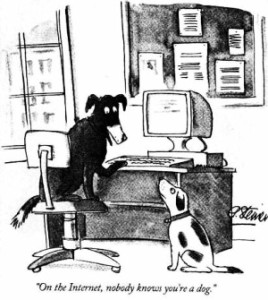

The short answer to this question is, “not really.” The nature of the Web makes it possible to share and comment on just about anything, whether or not owners, writers, and publishers like it. Similar to how digital versions of literature allow texts to become fluid which enables two-way “communication,” readers who are eager to join into the conversation find commenting to be a useful vehicle. Sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and many others allow users to share their opinions on content independent of its original source, and if the commenter is using a screen name that does not connect to their identity, then it’s still relatively anonymous. This post on Reddit discusses why it is unsafe to use one’s actual name online, responding to one user’s question, “When commenting online, why don’t you use your real name?”  Though it is clear some people are concerned about Web safety for purposes like identity theft, to me, it seems more likely to be an issue of accountability; when a user leaves a comment anonymously, there is a sort of pseudo-invincibility that occurs, because the user knows that the consequences of whatever they’ve said are almost sure to be limited. So perhaps it is still an issue of safety, but a different kind of safety that protestors, trolls, cyberbullies, and just-plain-rude commenters are worried about.

Though it is clear some people are concerned about Web safety for purposes like identity theft, to me, it seems more likely to be an issue of accountability; when a user leaves a comment anonymously, there is a sort of pseudo-invincibility that occurs, because the user knows that the consequences of whatever they’ve said are almost sure to be limited. So perhaps it is still an issue of safety, but a different kind of safety that protestors, trolls, cyberbullies, and just-plain-rude commenters are worried about.

Pros and Cons of Anonymity and the Effect of Removing Comments

Interestingly, around the same time last year when Popular Science and The Huffington Post so controversially changed their commenting policies, an article came out in The New Yorker called “The Psychology of Online Comments.” This piece deals with “cyberpsychology,” and makes reference to a study done in 2004 in which one researcher coins the term “Online Disinhibition Effect“: “The theory is that the moment you shed your identity the usual constraints on your behavior go, too,” says the New Yorker article. (Four years later, in 2008, another study came out entitled Self-disclosure on the Internet: the effects of anonymity of the self and the other.  Admittedly, I haven’t read either of these studies closely, but the fact that they [and probably countless others] exist means that researchers are identifying a measurable phenomenon worth looking into and talking about, because as we have discussed in class, technology shapes people, including their thoughts and behaviors.) The article in The New Yorker goes on to reference a study in which this was found: “Anonymity made a perceptible difference: a full fifty-three per cent of anonymous commenters were uncivil, as opposed to twenty-nine per cent of registered, non-anonymous commenters. Anonymity, Santana concluded, encouraged incivility.”

Admittedly, I haven’t read either of these studies closely, but the fact that they [and probably countless others] exist means that researchers are identifying a measurable phenomenon worth looking into and talking about, because as we have discussed in class, technology shapes people, including their thoughts and behaviors.) The article in The New Yorker goes on to reference a study in which this was found: “Anonymity made a perceptible difference: a full fifty-three per cent of anonymous commenters were uncivil, as opposed to twenty-nine per cent of registered, non-anonymous commenters. Anonymity, Santana concluded, encouraged incivility.”

Despite the notable ramifications of anonymity, the article also mentions some positive effects of being anonymous online, such as increased participation, a greater sense of community identity, and boosts in creative thinking and problem solving. Though face-to-face communication has been found to produce greater “satisfaction,” anonymous online communication allows for greater risk-taking for individuals. Additionally, The New Yorker shows that anonymous comments tend to be taken less seriously, and therefore rarely impact the course of a conversation in terms of changing someone’s initial perceptions. This is probably because it is more difficult to affirm the credibility of an anonymous user.

In many of our discussions about Walden, we identity contemporary issues as being “old wine in new bottles,” because we recognize that many common problems have always existed, but simply look different because of how people and technology have evolved; this situation is no different. The following quote comes from the same article I’ve been discussing from The New Yorker: In a study, “The authors found that the nastier the comments, the more polarized readers became about the contents of the article, a phenomenon they dubbed the ‘nasty effect.’ But the nasty effect isn’t new, or unique to the Internet. Psychologists have long worried about the difference between face-to-face communication and more removed ways of talking – the letter, the telegraph, the phone. Without the traditional trappings of personal communication, like non-verbal cues, context, and tone, comments can become overly impersonal and cold.”

When thinking about whether or not banning comments will truly solve the problem, an interesting note to keep in mind is that in doing so, the idea of “shared reality” becomes lessened, and therefore the interest surrounding that particular content decreases as well. The New Yorker article states, “Take away comments entirely, and you take away some of that shared reality, which is why we often want to share or comment in the first place. We want to believe that others will read and react to our ideas. What the University of Wisconsin-Madison study may ultimately show isn’t the negative power of a comment in itself but, rather, the cumulative effect of a lot of positivity or negativity in one place, a conclusion that is far less revolutionary.” It seems that this sort of “mob mentality” is nothing new, it merely looks different because it’s on a screen. But is it any more or less acceptable this way? Especially relevant to consider is that fact that the members of this cyber mob very well might be hidden behind the shield of anonymity.

When thinking about whether or not banning comments will truly solve the problem, an interesting note to keep in mind is that in doing so, the idea of “shared reality” becomes lessened, and therefore the interest surrounding that particular content decreases as well. The New Yorker article states, “Take away comments entirely, and you take away some of that shared reality, which is why we often want to share or comment in the first place. We want to believe that others will read and react to our ideas. What the University of Wisconsin-Madison study may ultimately show isn’t the negative power of a comment in itself but, rather, the cumulative effect of a lot of positivity or negativity in one place, a conclusion that is far less revolutionary.” It seems that this sort of “mob mentality” is nothing new, it merely looks different because it’s on a screen. But is it any more or less acceptable this way? Especially relevant to consider is that fact that the members of this cyber mob very well might be hidden behind the shield of anonymity.

But What about My Rights? What about Free Speech?

Coming back now to the USA Today article from this week, one significant debate that is arising out of the comment bans is whether or not it impedes on civil liberties to do so. The article quotes senior staff attorney Matt Zimmerman as saying, “I think (anonymity is) an important legal right that needs to be protected.” Despite this, “Zimmerman acknowledges that there is no legal issue with sites deciding what kind of commenting culture they want to cultivate, and that opportunities for people to contribute anonymously are abundant.” So the right to decide what (if any) types of comments are allowed on a site legally belongs to the people who run the site, a probably obvious point. Of course this opens the door to issues of control and censorship, which is another topic altogether. But what about free speech?

In terms of free speech, limitations exist no matter what the context, and the specific problem with being anonymous is accountability. The Huffington Post defended their decision to remove anonymous comments by saying, “Freedom of expression is given to people who stand up for what they’re saying and who are not hiding behind anonymity.” The Web allows users to wear masks in a way non-digital spaces do not, and if someone is extremely tech-savvy, they can get away with saying almost anything without leaving a trace. For a simple example, digital footprints become muddied when someone uses a public computer in a busy place without any surveillance equipment – this example doesn’t even begin to skim the surface of other methods of covering up one’s identity online. John Wooden once said, “The true test of a man’s character is what he does when no one is watching.” What about when people are watching, but don’t know who the man is? Can the same be said for him in that situation? If so, does a user still have the right to free speech without the ability to be identified or held accountable for his or her actions in cyberspace? I assume legislation will have to become much more specific about this in the future, especially if issues of diffused responsibility get too out of hand. Or do you think they are already?

We’ve talked a lot about how digital technology affects our interpretation of texts. We’ve also talked about how it alters the way in which we read texts by changing the medium through which those texts are delivered or on which they are assessed.

We’ve talked a lot about how digital technology affects our interpretation of texts. We’ve also talked about how it alters the way in which we read texts by changing the medium through which those texts are delivered or on which they are assessed.