At long last, my digital humanities project, “The Sandstone Trail,” is complete. With it, I had set out to create an archive of noteworthy buildings that utilized the famed Medina Sandstone in New York. I wanted not only to organize an archive with key metadata, but to also provide a visualization of this information. This visualization is key, and differs from traditional humanities, because it captures the scope of how popular Medina Sandstone was. It is one thing to read that it was used across New York, but another to physically see the locations of the buildings, and what they look like. Each of the 21 buildings featured also include a brief history, as well as metadata that pertains to their location, architect, date of construction, function, and more. This information is easily accessed via the map by clicking on the locations, or through the “Browse Items” tab on the homepage. This archival method is superior to a traditional humanities method, because it provides an interface that allows users to search by tags, and links relevant metadata directly to the post, so that the user does not have to search elsewhere for it.

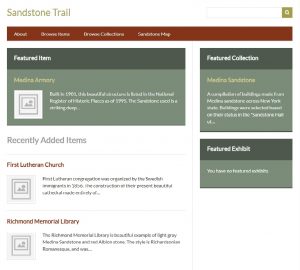

The site itself is also laid out to be very user friendly. Along the top are four tabs titled, “About,” “Browse Items,” “Browse Collections,” and “Sandstone Map.” The “About” tab includes some background on Medina Sandstone, and the relevance of the project. The “Browse Items” tab allows users to, as the name implies, browse the various buildings that are featured. Users may narrow their search by clicking on “Browse by Tag,” so that they may find buildings specific to one area, such as Buffalo or Rochester. “Browse Collections” includes the only collection that is available on the site, the “Medina Sandstone’ collection, which holds all the buildings. And last but not least is the “Sandstone Map,” which opens the Neatline powered map that enables users to go around New York State to look at the various buildings. From there, they can click on the numerous dots to view the history of the building, metadata, and a link to its page in the archive.

However, this progress was not achieved without some road bumps along the way. My initial problems were just getting Omeka to even run on my machine; thankfully, a trip to Dr. Kirk Anne was able to solve the issue. I had (and still have) problems getting ImageMagick to work, which would allow thumbnails of my images to appear on screen. Apparently, this is a Windows specific issue, which is unfortunate because it limits the aesthetic element of my project, but fortunately they can still be viewed, albeit not in a nicely formatted thumbnail. Adversity was also met in getting the Neatline map to function properly. Dr. Schacht and I were able to fix this, but even after leaping that hurdle, there came the problem of pinpointing the building locations. Unfortunately, Neatline does not follow the same coordinate language as Google Maps (where I pulled my information from) so I was not able to upload that and have a point placed on the map. Instead, I had to drop the pins for each building manually, and make approximations based off their location on Google Maps. It ended up working out fine in the end, but it was a very time-consuming process.

Overall, this project has allowed me to explore a method of presenting information that I would have thought impossible. In the case of my project, I have been able to represent an archive that would previously be represented only by text, and provide visual data to enhance the overall information that can be garnered. I was not well-versed in utilizing computer programs such as Omeka and MAMP, and now I not only know how to use them, but I understand just how beneficial they are in transcending the limitations of traditional humanities projects, so that they can become more accessible and informative.