It’s no secret that the current generation is the most technologically advanced that the human race has ever seen. It shouldn’t come as a surprise to learn that the ways in which technology has become integrated into our lives are far more varied and critical than ever before. Even so, every once in a while we can still learn something knew about our digital world that manages to surprise us.

In one of the most recent episodes of Radiolab, an online radio show sponsored by NPR, the hosts tackle the rising conflict between our online social presence, and human emotion. By looking at a series of social science studies conducted over the social media site Facebook, they try to answer the question of which is currently more important to us as a society: true human contact, or the power of the web.

The episode, titled “The Trust Engineers,” reveals that there is a lot more to Facebook than chatting and getting news about your friends. Over the past years, Facebook has grown not only to be one of the largest communities ever to exist on Earth, it has also become one of the leading centers for social science research. One of its most commonly pursued topics of study is the way in which human beings use it to communicate.

A lot of people have mixed feelings about news like this. There are plenty of pros and cons to consider when a social media site starts pulling on our strings in the name of science. Starting with the pros, Facebook is massive. According to the podcast, as of March 2014 there were about 1.3 billion active users on Facebook, making it one of the planet’s largest communities even if it is just online. This gives researchers an immense population to pull from when conducting studies. On top of its size, Facebook’s population is completely random as well. It ignores borders of language, country and race, socioeconomic background, religion and sexual identity. This all but eliminates bias in the research population.

And then there are the cons. While Facebook is extremely effective as a population for research, it is also a threat to individual privacy. While many people may assume that Facebook could be using their information to give to advertisers or even in studies such as these, not everyone knows the extent to which this occurs. According to researchers, every single Facebook user has been used in one of their studies, and on average every active user’s information is being used in about ten different studies at any given moment. Whether you were aware of it or not, or whether you agree with it or not, you are most likely participating in ten different social experiments right now.

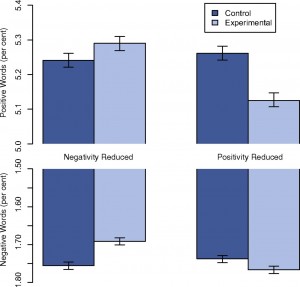

One of Facebook’s most controversial studies came at the beginning of summer in 2014, when it was revealed that Facebook had conducted a wide study of human emotion on several thousands of its users. Facebook wanted to see if it could manipulate the emotions of its users by showing them an increased number of either positive or negative posts, and measuring how their own posts changed as a result of this. They wanted to see if they could digitally spread positivity or negativity by manipulating people’s news feeds. While the results of this experiment were inconclusive, the backlash from users was immense.

Facebook is two things. It is an amazing, immense population unlike anything else humans have ever created, capable of changing the way we study ourselves forever. Unfortunately, it is also a great and threatening concentration of power and control over its users, most of whom are at least partially unaware of the extent to which Facebook is capable of affecting them. All of this begs the question: which is more important to us, having information about everything at our fingertips, or keeping information about ourselves away from everyone else? Technology such as this can be a great aid in our understanding of how human emotion operates, but where do we draw the line between attempting to understand emotion and attempting to replace it?